On determining the outer shell of a unit cube complex

Table of Contents

Christodoulos Fragkoudakis and Markos Karampatsis

This report results from our research and development during our secondment in IDEA75 between 1/6/2021 and 31/11/2021. Our work program was “WP1” “Development of topology-sizing design optimization methodology incorporating nonlinear FEM analyses and machine learning” as described in Annex 1 of the Grant Agreement.

A Python class for 3D Points #

We will assemble a python class that represents 3D points and supports basic operations between its instances. We initialize an object of the Point class using three parameters, x, y, and z, the respective cartesian coordinates. The “coordinates” class property returns a three-valued Python tuple comprising the x, y, and z coordinates. We define two more methods to initialize the class, the from_point method that initializes a point instance from another point instance and the from_tuple method that initializes a point instance from a three-valued Python tuple. We represent a Point instance using the respective Point(x,y,z) string and define the _hash_ function that ensures that two equal Point instances always return the same values.

class Point(object):

"A class for 3D points"

def __init__(self, x, y, z):

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.z = z

@classmethod

def from_point(cls, point):

"Initializes a 3D point from another point"

return cls(point.x, point.y, point.z)

@classmethod

def from_tuple(cls, tup):

"Initializes a 3D point from a tuple of 3 values"

return cls(tup[0], tup[1], tup[2])

@property

def coordinates(self):

"Returns the coordinates of the 3D point"

return self.x, self.y, self.z

def __repr__(self):

return 'Point({0},{1},{2})'.format(self.x, self.y, self.z)

def __hash__(self):

return hash((self.x, self.y, self.z))

Three-dimensional points, i.e., instances of the Point class, have the usual ordering according to their “coordinates” property. Two Point instances are equal if their coordinates tuples are equal, accordingly when they are not equal. A Point instance is “less” than another instance if the corresponding tuples have the exact ordering, respectively, when a Point instance is “greater” than another instance. We utilize Python tuples that inherently support lexicographic order to implement the above reasoning.

Our Point class supports coordinate iteration by the __iter__ function, while positional coordinate getting and setting are possible, using the __getitem__ and __setitem__ functions.

def __eq__(self, other):

if not other:

return False

return (self.x, self.y, self.z) == (other.x, other.y, other.z)

def __ne__(self, other):

if not other:

return True

return (self.x, self.y, self.z) != (other.x, other.y, other.z)

def __lt__(self, other):

return (self.x, self.y, self.z) < (other.x, other.y, other.z)

def __gt__(self, other):

return (self.x, self.y, self.z) > (other.x, other.y, other.z)

def __le__(self, other):

return (self.x, self.y, self.z) <= (other.x, other.y, other.z)

def __ge__(self, other):

return (self.x, self.y, self.z) >= (other.x, other.y, other.z)

def __getitem__(self, index):

return (self.x, self.y, self.z)[index]

def __setitem__(self, index, value):

temp = [self.x, self.y, self.z]

temp[index] = value

self.x, self.y, self.z = temp

def __iter__(self):

yield self.x

yield self.y

yield self.z

def __sub__(self, other):

"Subtracts two points giving the vector that anslates other to self."

return Vector(other.x - self.x, other.y - self.y, other.z - self.z)

def __add__(self, vector):

"Translates self to another points using 'vector' vector"

return Point(self.x + vector.x, self.y + vector.y,

self.z + vector.z)

Finally, our Point class supports subtraction between its instances and adding a Vector instance (to be defined later) to a Point instance. If we subtract two Point instances, we get the Vector that translates the first instance to the second. If we add a Vector instance to a Point instance, we get the translated Point instance.

A Python class for 3D Vectors #

Our Python class for 3D Vectors inherits the Point class and implements the essential property of magnitude. Notice that there is no need to employ a costly square root operation as two vectors have the same extent if the respective squared number is the same for both. Our class also supports the cross-product operation between two instances by a straightforward calculation of 6 multiplications and three additions.

class Vector(Point):

"A class for 3D Vectors"

def __init__(self, *args):

if not args:

x, y, z = 0, 0, 0

elif len(args) == 1:

if args[0].__class__ is Point:

x, y, z = args[0].x, args[0].y, args[0].z

else:

x, y, z = args[0], 0, 0

elif len(args) == 2:

x, y, z = args[0], args[1], 0

else:

x, y, z = args[0], args[1], args[2]

self.coords = [x, y, z]

super(Vector, self).__init__(x, y, z)

def __repr__(self):

return "Vector({1},{2},{3})".format(self.x, self.y, self.z)

@property

def magnitude2(self):

"Returns the squared magnitude of the vector."

return self.x**2 + self.y**2 + self.z**2

def cross(self, vector):

"Returns the cross product of self and vector"

return Vector(

(self.y * vector.z - self.z * vector.y),

(self.z * vector.x - self.x * vector.z),

(self.x * vector.y - self.y * vector.x))

An example usage of the Point and Vector classes in the Python interpreter is the following:

>>> from ucc2stl import Point, Vector

>>> x = Point(1,2,3)

>>> y = Point(4,5,6)

>>> x-y

Vector(3,3,3)

>>> z = Vector(3,3,3)

>>> x+z

Point(4,5,6)

Unit cube complexes #

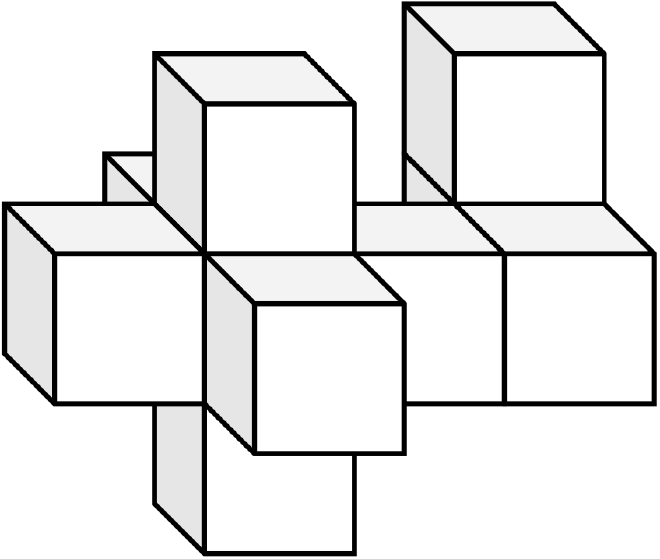

The traditional Finite Element approach discretizes a continuous orthogonal domain into more minor elements of a specific shape. We consider unit cube complexes produced by various finite element analysis models. The constructed complexes are dense, and to 3D print them, we need to determine their outer shell, i.e., to calculate the complex’s surface geometry.

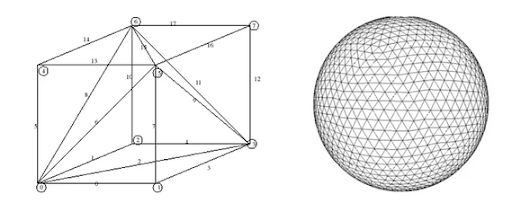

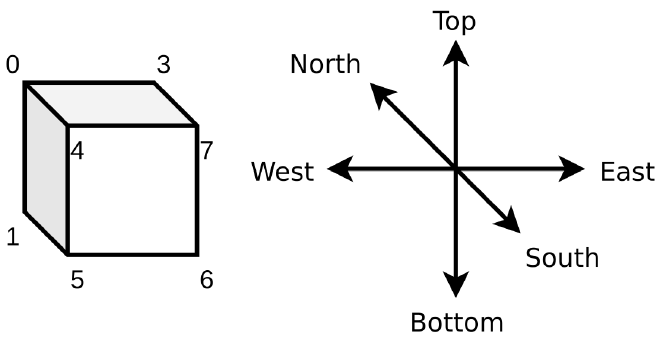

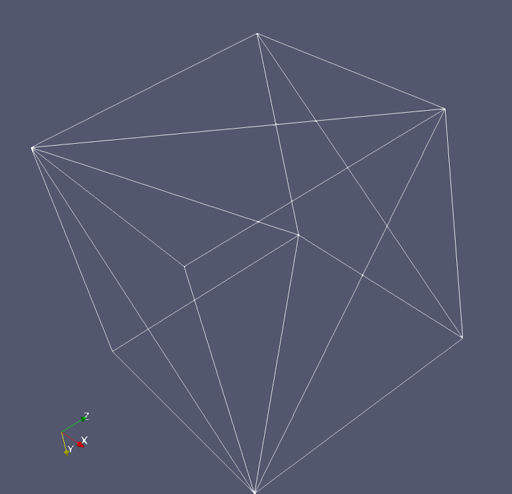

The unit cube complex’s surface is already a tesselation comprised of rectangles that have no overlaps or leave no gaps. Our purpose is to employ the STL file format specification, which is to tessellate the outer surface of the complex using triangles and store information about the triangles in a file. For example, the unit cube in the following image has two triangles per face, and since the cube has six faces, it adds up to twelve triangles. Many small triangles can also cover a 3D model of a sphere with a corresponding STL representation. Curved objects are out of the scope of our research, so that we will stick to rectangular constructions.

Let us fix a data structure that represents unit cubes. Consider a unit cube aligned to the cartesian coordinate system and that the “xz” plane represents a traditional map where the common practice defines the four points of the horizon. There are six primary directions towards each cube’s face: north, south, east, west, top, and bottom. We label the cube’s faces according to the direction.

We represent each labeled cube face as a counterclockwise or clockwise list of its vertices regarding its interior. We use a counterclockwise listing when the interior is below, left of, or behind the face. We use a clockwise listing when the interior is above, right, or in front of the face:

- The north face is \(0321\)

- The south face is \(4567\)

- The east face is \(6512\)

- The west face is \(0473\)

- The top face is \(3762\)

- The bottom face is \(1265\)

The centroid of a unit cube is simply the arithmetic mean of its vertices, and we calculate it twenty-four additions and three divisions:

$$ c=(x,y,z) = \left( \frac{\sum_{i=1}^8}{8}x_i, \frac{\sum_{i=1}^8}{8}y_i, \frac{\sum_{i=1}^8}{8}z_i \right) $$

We realize the centroid as the vector from \((0,0,0)\) towards the \((x,y,z)\) point. Given two unit cubes \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) in 3D space, there is a well-defined ordering if we consider the relative positions of the cubes’ centroids. We say that the unit cube \(C_2\) is “bigger than” the unit cube \(C_1\) if and only if their centroids respect the exact ordering \(c_2>c_1\). The relative position of the cube \(C_2\) might be right, or on top or, in front of the cube \(C_1\). The same reasoning also applies when we try to locate the immediate next of the unit cube \(C\) with centroid \(c\) along each of the \(x\), \(y\), \(z\) axes:

- The west cube is around \((x+1,y,z)\)

- The top cube is around \((x,y+1,z)\)

- The south cube is around \((x,y,z+1)\)

- Similarly, for the east, bottom, and north cubes.

A Python class for unit cubes #

Let us start by implementing a class that realizes the unit cube’s faces. Our unit cube complexes also comprise instances of collections of such faces, so it seems reasonable to define the normal function as a method that returns a Vector instance perpendicular to the respective plane.

class Face(object):

"A general representation of a complex's face"

def __init__(self, vertices):

"self.vertices is an iterable of Point"

self.vertices = vertices

def __repr__(self):

_repr = "\nFace\n"

for vertex in self.vertices:

_repr += "\t%s\n" % vertex

return _repr

def normal(self):

"A vector perpendicular to the face"

v = self.vertices

v1 = v[0] - v[1]

v2 = v[0] - v[2]

return v1.cross(v2)

A cuboid is a collection of six faces, the north, south, east, west, top, and bottom. We implement the face dictionary using the definitions given above: the face representation is a counterclockwise listing of its vertices when the interior of the cuboid is below, left, or behind the face. Otherwise, it is a clockwise listing of vertices. The centroid of the cuboid is the weighted average of the cuboid’s vertices.

We compare cuboids by utilizing the already implemented comparison between instances of the Point class. So to compare cuboids, we compare their centroids using the reasoning we described above. To translate an instance relative to a given vector v, we simply iterate over the vertices and translate each vertex using the given vector.

class Cuboid(object):

"A class for cuboids"

def __init__(self, vertices):

self.vertices = sorted(vertices)

v = self.vertices

self.facedict = {

"north": Face([v[0], v[2], v[6], v[4]]),

"south": Face([v[1], v[5], v[7], v[3]]),

"east": Face([v[5], v[4], v[6], v[7]]),

"west": Face([v[0], v[1], v[3], v[2]]),

"top": Face([v[6], v[2], v[3], v[7]]),

"bottom": Face([v[0], v[4], v[5], v[1]]),

}

def __repr__(self):

_repr = "\nCuboid:\n--------\nVertices\n--------\n"

for vertex in self.vertices:

_repr += "\t%s\n" % vertex

_repr += "-----\nFaces\n-----\n"

for orientation, face in self.faces:

_repr += "{0}: {1}".format(orientation, face)

return _repr

def __eq__(self, other):

return self.centroid == other.centroid

def __ne__(self, other):

return self.centroid != other.centroid

def __lt__(self, other):

return self.centroid < other.centroid

def __qt__(self, other):

return self.centroid > other.centroid

def __le__(self, other):

return self.centroid <= other.centroid

def __ge__(self, other):

return self.centroid >= other.centroid

@property

def faces(self):

"docstring"

for orientation, face in self.facedict.items():

yield orientation, face

@property

def centroid(self):

"Returns the centroid of the cuboid"

x, y, z = 0.0, 0.0, 0.0

for vertex in self.vertices:

x += vertex.x

y += vertex.y

z += vertex.z

return Point(x / 8.0, y / 8.0, z / 8.0)

def translate(self, vector):

translated = [vertex + vector for vertex in self.vertices]

return Cuboid(translated)

Let us use our classes and create two cuboids. We make the first one by explicitly defining its eight vertices, while the second one is a translation of the first using the \((1,1,1)\) vector. We print the cuboids and finally check their order.

from ucc2stl.cuboids import Cuboid

from ucc2stl import Point, Vector

x0 = Point(0, 0, 0)

x1 = Point(1, 0, 0)

x2 = Point(1, 1, 0)

x3 = Point(0, 1, 0)

x4 = Point(0, 0, 1)

x5 = Point(1, 0, 1)

x6 = Point(1, 1, 1)

x7 = Point(0, 1, 1)

cuboid0 = Cuboid([x0, x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7])

vector = Vector(1, 1, 1)

cuboid1 = cuboid0.translate(vector)

print(cuboid0, cuboid1)

print(cuboid0.centroid, cuboid1.centroid, cuboid0 < cuboid1, cuboid0 > cuboid1)

We include the above script’s output by representing the cuboids side by side for comparison and space economy.

Cuboid: Cuboid:

-------- --------

Vertices Vertices

-------- --------

Point(0,0,0) Point(1,1,1)

Point(0,0,1) Point(1,1,2)

Point(0,1,0) Point(1,2,1)

Point(0,1,1) Point(1,2,2)

Point(1,0,0) Point(2,1,1)

Point(1,0,1) Point(2,1,2)

Point(1,1,0) Point(2,2,1)

Point(1,1,1) Point(2,2,2)

---------- ----------

north Face north Face

---------- ----------

Point(0,0,0) Point(1,1,1)

Point(0,1,0) Point(1,2,1)

Point(1,1,0) Point(2,2,1)

Point(1,0,0) Point(2,1,1)

---------- ----------

south Face south Face

---------- ----------

Point(0,0,1) Point(1,1,2)

Point(1,0,1) Point(2,1,2)

Point(1,1,1) Point(2,2,2)

Point(0,1,1) Point(1,2,2)

--------- ---------

east Face east Face

--------- ---------

Point(1,0,1) Point(2,1,2)

Point(1,0,0) Point(2,1,1)

Point(1,1,0) Point(2,2,1)

Point(1,1,1) Point(2,2,2)

--------- ---------

west Face west Face

--------- ---------

Point(0,0,0) Point(1,1,1)

Point(0,0,1) Point(1,1,2)

Point(0,1,1) Point(1,2,2)

Point(0,1,0) Point(1,2,1)

-------- --------

top Face top Face

-------- --------

Point(1,1,0) Point(2,2,1)

Point(0,1,0) Point(1,2,1)

Point(0,1,1) Point(1,2,2)

Point(1,1,1) Point(2,2,2)

----------- -----------

bottom Face bottom Face

----------- -----------

Point(0,0,0) Point(1,1,1)

Point(1,0,0) Point(2,1,1)

Point(1,0,1) Point(2,1,2)

Point(0,0,1) Point(1,1,2)

Point(0.5,0.5,0.5) Point(1.5,1.5,1.5) True False

A Python class for cuboid complexes #

We are now ready to capitalize on our already made classes and assemble a Python class that handles unit cube complexes in 3D space. We initialize an instance of CuboidComplex by passing as a parameter an iterable of cuboids, each indexed using its centroid into the instance’s cubdict attribute. We initialize the triangle and vertex lists that comprise the final complex as empty lists.

class CuboidComplex(object):

""" A class that handles unit cube complexes in 3D space """

def __init__(self, cuboids):

self.cubdict = dict()

self.shell_triangles = list()

self.shell_vertices = list()

print("Started inserting cuboids ... ", end="")

for cuboid in cuboids:

self.insert(Cuboid(cuboid))

print("Done inserting {} cuboids".format(len(cuboids)))

Let us focus on the insert method that uses the cubdict dictionary to hold the data of the inserted cuboids, indexed by their centroid. The dictionary’s key is the cuboid’s centroid, while the data indexed is another dictionary indexed by the cuboid’s faces orientation. The indexed data are the face itself and a boolean indication of whether it is outer or not. Imagine here that we need to insert every given cuboid and that the very first cuboid comprises a complex with six outer faces.

Our next task is to identify all the immediate neighbors of the inserted cuboid. Our cubdict dictionary is a handy construct as we can locate them by looking towards the six faces orientation of the inserted cuboid. To that direction, we calculate the neighbors’ indexes, i.e., the neighbors’ centroids, as already described. If the currently inserted cuboid has actual neighbors in the complex, their centroids must already be indexes of the cubdict dictionary.

Our last task is to update the complex’s faces’ boolean out indicator. If a cuboid is on top of the inserted one, then the inserted cuboid’s top face and the neighbor’s bottom face reside inside the complex. If there is a cuboid west of the inserted one, then the inserted cuboid’s west face and the neighbor’s east face both reside inside the complex. The same reasoning applies to every other direction by refreshing the touching faces as inside ones, i.e., updating the boolean out indicator. These operations are well-defined and repeatedly performed for every inserted cuboid. It must now be evident that after the insertion of the last cuboid, our cubdict construct holds all the complex’s faces, and for every face, the correct indicator of whether the face is outer or not.

def insert(self, cuboid):

""" Inserts a cuboid into the complex keeping track of outer Faces """

cuboid_id = cuboid.centroid # id is an instance of Point

self.cubdict[cuboid_id] = {}

for orientation, face in cuboid.faces:

self.cubdict[cuboid_id][orientation] = {"face": face, "out": True}

x, y, z = cuboid_id.x, cuboid_id.y, cuboid_id.z

top_id = Point(x, y + 1, z)

bottom_id = Point(x, y - 1, z)

west_id = Point(x - 1, y, z)

east_id = Point(x + 1, y, z)

north_id = Point(x, y, z - 1)

south_id = Point(x, y, z + 1)

if top_id in self.cubdict:

self.cubdict[top_id]["bottom"]["out"] = False

self.cubdict[cuboid_id]["top"]["out"] = False

if bottom_id in self.cubdict:

self.cubdict[bottom_id]["top"]["out"] = False

self.cubdict[cuboid_id]["bottom"]["out"] = False

if west_id in self.cubdict:

self.cubdict[west_id]["east"]["out"] = False

self.cubdict[cuboid_id]["west"]["out"] = False

if east_id in self.cubdict:

self.cubdict[east_id]["west"]["out"] = False

self.cubdict[cuboid_id]["east"]["out"] = False

if north_id in self.cubdict:

self.cubdict[north_id]["south"]["out"] = False

self.cubdict[cuboid_id]["north"]["out"] = False

if south_id in self.cubdict:

self.cubdict[south_id]["north"]["out"] = False

self.cubdict[cuboid_id]["south"]["out"] = False

We are now ready to calculate the complex’s outer shell vertices and triangles. To that end, we iterate over the cubdict dictionary items. We are only interested in outer faces, so we take action only when we find an appropriate out indicator. A local vdict dictionary construct keeps track of already found vertices to avoid inserting the same vertex to the shell’s vertices list more than once. When we process an outer face, we iterate over its vertices to update the shell’s vertices and identify the two triangles that comprise the face. We finally insert the triangles into the shell’s triangle list.

def shell(self):

""" Calculates the outer shell vertices and triangles """

print("Started outer shell calculation ... ", end="")

vdict = dict()

nvs = -1

for cuboid, faces_info in self.cubdict.items():

for face_label, face_info in faces_info.items():

if face_info["out"]:

tface = []

for vertex in face_info["face"].vertices:

coords = (vertex.x, vertex.y, vertex.z)

if coords not in vdict:

nvs += 1

self.shell_vertices.append(coords)

vdict[coords] = nvs

tface.append(vdict[coords])

tri1 = [tface[0], tface[1], tface[2]]

tri2 = [tface[2], tface[3], tface[0]]

self.shell_triangles += [tri1, tri2]

print(

"Done\nThere are {} vertices and {} triangles".format(

len(self.shell_vertices), len(self.shell_triangles)

)

)

To export the shell’s representation into the STL file format, we use the excellent numpy-stl Python module. We import the module’s mesh library that constructs STL meshes by utilizing our already calculated list of shell’s vertices and triangles. We save the calculated mesh to the model.stl file.

def export_stl(self):

vertices = np.array(self.shell_vertices)

faces = np.array(self.shell_triangles)

stlmesh = mesh.Mesh(np.zeros(faces.shape[0], dtype=mesh.Mesh.dtype))

for i, f in enumerate(faces):

for j in range(3):

stlmesh.vectors[i][j] = vertices[f[j], :]

stlmesh.save("model.stl")

Test cases of unit cube complexes #

Let us now check various test cases regarding the usage of our CuboidComplex class. We will present the Python code and the resulting STL file. To produce the shown images, we inserted the generated STL mesh into the Paraview and exported the scene into a PDF file. Then we converted the PDF file to a PNG using the pdftoppm Linux utility.

A cube #

from ucc2stl.cuboids import Cuboid, CuboidComplex

from ucc2stl import Point, Vector

x0 = Point(0, 0, 0)

x1 = Point(1, 0, 0)

x2 = Point(1, 1, 0)

x3 = Point(0, 1, 0)

x4 = Point(0, 0, 1)

x5 = Point(1, 0, 1)

x6 = Point(1, 1, 1)

x7 = Point(0, 1, 1)

cuboid = Cuboid([x0, x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7])

complex = CuboidComplex([cuboid.vertices])

complex.shell()

complex.export_stl()

Started inserting cuboids ... Done inserting 1 cuboids

Started outer shell calculation ... Done

There are 8 vertices and 12 triangles.

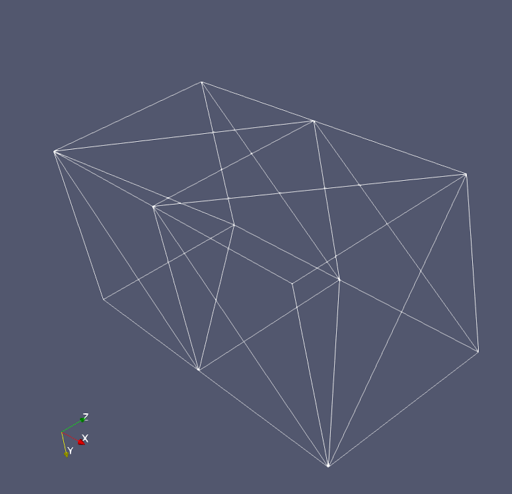

Two cubes side by side #

from ucc2stl.cuboids import Cuboid, CuboidComplex

from ucc2stl import Point, Vector

x0 = Point(0, 0, 0)

x1 = Point(1, 0, 0)

x2 = Point(1, 1, 0)

x3 = Point(0, 1, 0)

x4 = Point(0, 0, 1)

x5 = Point(1, 0, 1)

x6 = Point(1, 1, 1)

x7 = Point(0, 1, 1)

cuboid_list = []

cuboid0 = Cuboid([x0, x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7])

vector = Vector(1,0,0)

cuboid1 = cuboid0.translate(vector)

complex = CuboidComplex([cuboid0.vertices, cuboid1.vertices])

complex.shell()

complex.export_stl()

Started inserting cuboids ... Done inserting 2 cuboids

Started outer shell calculation ... Done

There are 12 vertices and 20 triangles.

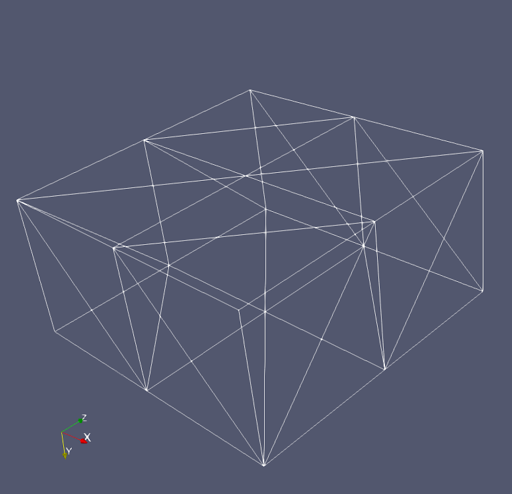

Four cubes side by side #

from ucc2stl.cuboids import Cuboid, CuboidComplex

from ucc2stl import Point, Vector

x0 = Point(0, 0, 0)

x1 = Point(1, 0, 0)

x2 = Point(1, 1, 0)

x3 = Point(0, 1, 0)

x4 = Point(0, 0, 1)

x5 = Point(1, 0, 1)

x6 = Point(1, 1, 1)

x7 = Point(0, 1, 1)

cuboid = Cuboid([x0, x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7])

cuboid_list = [cuboid]

translation_vectors = [

Vector(1, 0, 0),

Vector(0, 0, 1),

Vector(1, 0, 1)

]

for vector in translation_vectors:

cuboid_list.append(cuboid.translate(vector))

complex = CuboidComplex([cuboid.vertices for

cuboid in cuboid_list])

complex.shell()

complex.export_stl()

Started inserting cuboids ... Done inserting 4 cuboids

Started outer shell calculation ... Done

There are 18 vertices and 32 triangles.

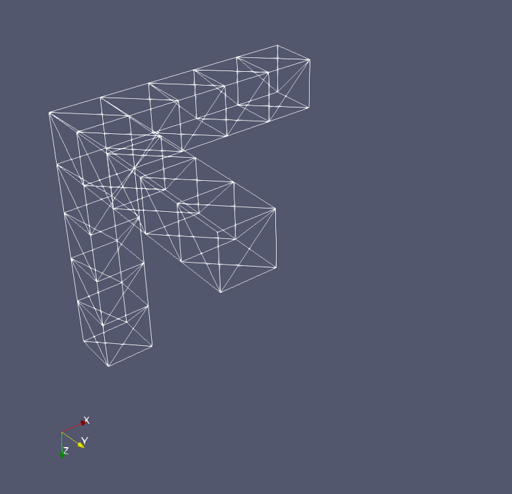

Three connected columns #

from ucc2stl.cuboids import Cuboid, CuboidComplex

from ucc2stl import Point, Vector

x0 = Point(0, 0, 0)

x1 = Point(1, 0, 0)

x2 = Point(1, 1, 0)

x3 = Point(0, 1, 0)

x4 = Point(0, 0, 1)

x5 = Point(1, 0, 1)

x6 = Point(1, 1, 1)

x7 = Point(0, 1, 1)

cuboid = Cuboid([x0, x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7])

cuboid_list = [cuboid]

for i in range(4):

current = Cuboid(cuboid.vertices)

for j in range(4):

current = Cuboid(cuboid.vertices)

for k in range(4):

if i == 0:

vector = Vector(1, 0, 0)

elif j == 0:

vector = Vector(0, 1, 0)

else:

vector = Vector(0, 0, 1)

current = current.translate(vector)

cuboid_list.append(current)

complex = CuboidComplex([cuboid.vertices for cuboid in cuboid_list])

complex.shell()

complex.export_stl()

Started inserting cuboids ... Done inserting 65 cuboids

Started outer shell calculation ... Done

There are 56 vertices and 108 triangles.

Converting the nodes, connectivity, density representation to Python lists #

A usual representation of finite element methods analysis results is the nodes-connectivity representation. As a result of an optimization process, there is an extra density parameter for every connectivity construct. We developed helper functions to convert this information to use Python lists representations.

def csv2list(afile, atype, prepend_dummy=False):

"afile is a csv file of atype values, returns a list of tuples"

print("Opening {} ... ".format(afile), end="")

alist = []

for line in open(afile):

line2list = line.strip().split(",")

if len(line2list) > 1:

alist.append(tuple(atype(i) for i in line2list))

else:

alist.append(atype(line2list[0]))

print("Read {} values".format(len(alist)))

if prepend_dummy:

alist.insert(0, (0, 0, 0))

return alist

def dense_cuboids(nodes_file, connectivity_file, density_file, threshold):

"""returns a list of the 'dense' cuboids"""

alist = []

nodes = csv2list(nodes_file, int, prepend_dummy=True)

connectivity = csv2list(connectivity_file, int)

density = csv2list(density_file, float)

print("Filtering dense cuboids ...", end="")

for atuple in zip(density, connectivity):

if atuple[0] - threshold > EPSILON: # cuboid is 'dense enough'

cuboid = []

for vertex in atuple[1]:

cuboid.append(Point.from_tuple(nodes[vertex]))

alist.append(cuboid)

print("Filtered {} dense cuboids".format(len(alist)))

return alist

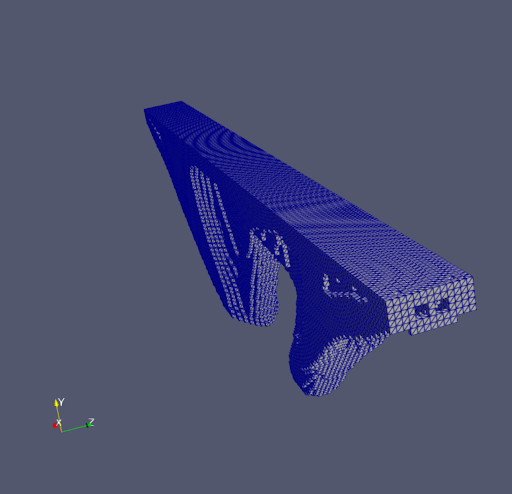

We had a set of nodes-connectivity-density files regarding the optimization output of a finite element analysis process. We utilized the above helper functions to convert this set of files to a suitable input of our CuboidComplex class.

from ucc2stl import dense_cuboids, CuboidComplex

cuboids = dense_cuboids("Node.txt", "Connectivity.txt", "density.txt", 0.3)

complex = CuboidComplex(cuboids)

complex.shell()

complex.export_stl()

Opening Node.txt ... Read 129444 values

Opening Connectivity.txt ... Read 117000 values

Opening density.txt ... Read 117000 values

Filtering dense cuboids ...Filtered 37148 dense cuboids

Started inserting cuboids ... Done inserting 37148 cuboids

Started outer shell calculation ... Done

There are 25264 vertices and 50572 triangles.

The picture of the resulting STL file output is the following: